Introduction to Mental Health Data

(Also available in Spanish)

- Mental Health

- Health Related Quality of Life (HRQOL)

- Poverty - A Risk Factor for Mental and Behavioral Health

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health

- Depression

- Anxiety and Stress

- Suicide

- Death from Suicide

- Suicide Attempts

- Cost

- Prevention - Mental Health Prevention Programs from SAMHSA

- Conclusion

- Appendix of Additional State and County-Level Information (with hyperlinks)

- Selected Bibliography (with hyperlinks to documents)

Mental Health

According to the CDC, well-being refers to how “people think and feel about their lives-the quality of their relationships, their positive emotions, resilience, satisfaction with life domains, or the realization of their potential.” Well-being can be measured by the extent to which a person feels positive emotions like happiness and tranquility and their interest in life and positive moods. It is also measured by the person’s sense of being connected with others through social ties and his/her sense of satisfaction and meaning in life. Measurement of well-being is expressed by the CDC as health related quality of life. (CDC, 2011a)

Mental disorders take many forms and can be very complicated and inter-related with physical health problems. Persons suffering from severe physical illnesses, chronic disease or traumatic injury are at high risk, for example, of developing mental illness due to poor quality of life. The types of mental disorders outlined by the National Institutes of mental health include anxiety disorders, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), autism, eating disorders, mood disorders, personality disorders, and schizophrenia. (NIMH, 2011d)

Health Related Quality of Life (HRQOL)

Because of the importance of well-being to health, surveillance of variables that measure health related quality of life have been gaining attention in the past two decades. The CDC has developed HRQOF measurements for every part of the lifespan for use in prevention, including in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), the Behavioral Risk Factor Survey (BRFSS) and the Porter Novelli Healthstyles Survey. In these surveys questions measure the individual's general well-being; global life satisfaction; satisfaction with emotional and social support; feeling happy in the past 30 days; meaning in life; autonomy, competence and relatedness; domain specific life satisfaction; and positive and negative affect. (CDC, 2011b)

Studying BRFSS survey data from 1993-2001, the CDC found frequent mental distress (FMD) to be a key indicator. FMD is measured as reporting 14 or more mentally unhealthy days in the past month. Besides its relationships to mental health, prevalence of FMD has also been found to be related to behaviors like smoking that are vital to the prevention of chronic disease. (CDC, 2011c)

Poverty - A Risk Factor for Mental and Behavioral Health

Socio-economic factors are weighted more heavily among health-related variables that impact health outcomes (morbidity and mortality). Social and economic factors include education, employment, income, family and social support and community safety. (The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation & University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute, 2011) Research has repeatedly affirmed that poverty is a major determinant of poor health. (Bloch, Rozmovits, & Giambrone, 2011). A relationship has been found between on-going high unemployment rates and heightened risks and incidence of suicide. (SAMHSA, 2011, p. NCMH/13.

Poverty is a growing problem in the U.S. According to an Index Mundi ranking that uses poverty statistics from the CIA World Factbook, twenty-two countries in the world report lower percent of their population living below the poverty line than the United States. (Index Mundi, 2011) According to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), measuring poverty as living below 50% of the median income, only Turkey and Mexico have higher poverty rates among the 34 countries tracked, and the U.S. is highest among the developed countries. (OECD, 2011)

As poverty increases or decreases, so do the indices of health problems (Bisgaier and Rhodes 2011) and social problems. (IOM Panel, 2011; IOM, 2009, p. 177; Duncan, Ziol Guest, & Kalil, 2010) According to the Institutes of Medicine, poverty is at least as important as other risk factors and may be the number one risk factor for children for problem development (IOM Panel, 2011):

Family poverty and the economic strains associated with such events as job loss frequently undermine family functioning. They are associated with multiple negative behavioral outcomes among children in these families, increase parental depression and spousal and parent-child conflict, and undermine effective parenting. (IOM, 2009, p. 176)

The National Center for Children in Poverty (NCCP) at Columbia University reports that nearly 15 million children live in families with income below the federal poverty level ($22,050 for a family of four -- two parents and two children). (NCCP, 2011) Child poverty is higher than ever in the past fifty years. Research from the Annie E. Casey Foundation (2011) finds 22% of US children in poverty in 2010 and reports increases in child poverty in 2010 across 38 states, including Indiana (at 22%) Moreover, poverty is not evenly distributed across population groups. Figures from Childstats.gov show that nearly 36% of Black children, compared with 33% of Hispanic and 12% of white children live below 100% Poverty. Children living in extreme poverty (below 50% poverty) consist 18% of Black children, 14% of Hispanic children and 5% of White children. (Child Stats.gov, 2011) According to the NCCP, "Research is clear that poverty is the single greatest threat to children's well-being."

In contrast to an earlier belief that poverty during adolescence was most damaging, recent research finds that experiencing poverty in early childhood (birth to age 5) creates greater risk for future poor health. Duncan, Kalil and Ziol-Guest found that children poor in their early years are more than two times more likely to suffer poor overall health and elevated stress levels as adults than children who do not experience poverty. (Duncan et al, 2010) Where parents are suffering financial duress, the entire family is impacted. Parents under stress from poverty argue more and the extremely important nurturing environment is strained. Some ways to combat poverty include a living wage, access to health care, increased benefits, food programs, and enterprise zones. (IOM Panel, 2011)

The challenge of poverty can be overcome. Mental, emotional and behavioral health is influenced by the interplay of the environment and genetic factors. Where children have considerable positive influences or protective factors in their environments, such as positive role models, strong early attachments and social relationships and personal characteristics (like self-regulatory control, communication and problem solving skills), they can achieve healthy development. (IOM, 2009; Leve, Fisher, & Chamberlain, 2009) These resilient young people can continue to thrive and from their experience of poverty gain a heightened capacity for comprehension, empathy and inspiration.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health

Substance abuse and addiction are associated with mental health consequences. A causative relationship exists between alcohol addiction and depression whereby greater involvement with alcohol raises risk of depression. (Boden & Fergusson 2011) Depression, in turn, raises the risk of addiction. (Lançon, 2010) Substance abuse is second only to depression in its association with suicide. (Saunders, 2008; CDC, 2009; AFSP, 2011a) and comorbidity of alcohol abuse and depression increases the risk (AFSP, 2011b) The rate of suicide deaths has been found to be associated with alcohol policy in studies done in Slovenia (Pridemore & Snowden, 2009) and in Ireland. There are shared risk factors among youth who die by suicide and those who die in alcohol-related accidents. (McKeon, 2011)

The following are excerpts from the CDC MMWR (2009) that drew data from 17 states, including Kentucky and Wisconsin.

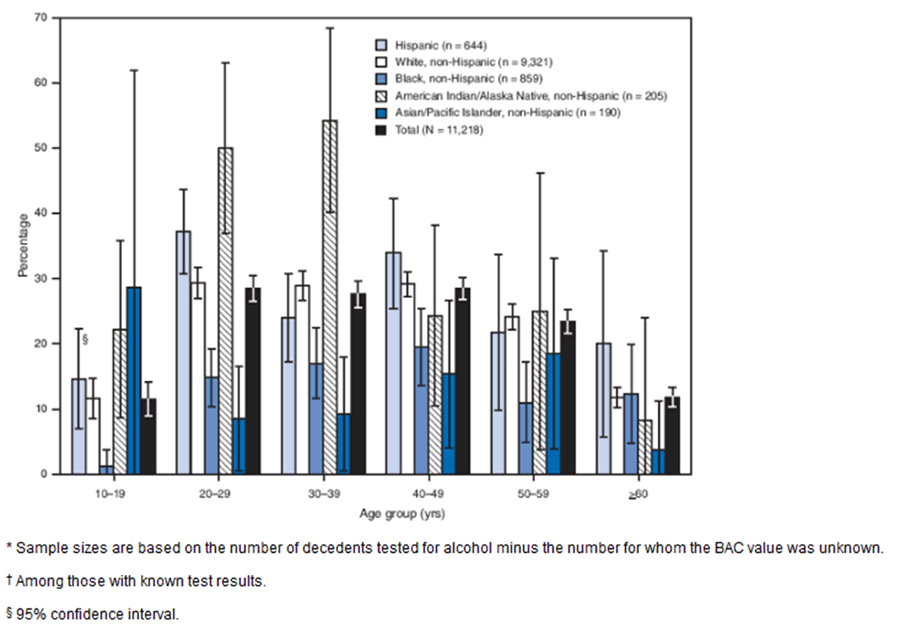

The figure above shows the percentage of suicide decedents with blood alcohol concentrations (BAC) >0.08 g/dL, by race/ethnicity and age group for 17 states during 2005-2006, according to the National Violent Death Reporting System. For all age groups, the highest proportion of decedents with BACs >0.08 g/dL was among American Indians/Alaska Natives (AI/ANs) aged 30-39 years, followed by AI/AN and Hispanic decedents aged 20-29 years. Among decedents tested who were aged 10-19 years (all of whom were under the legal drinking age in the United States), 12% had BACs >0.08 g/dL; the levels ranged from 1% in non-Hispanic blacks to 29% in non-Hispanic Asians/Pacific Islanders.

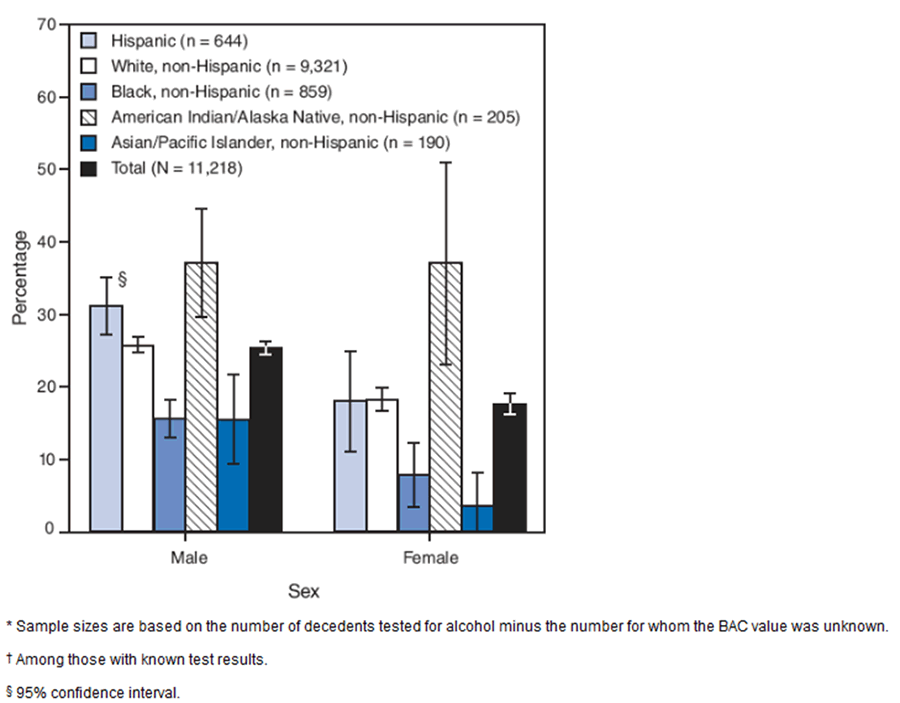

The figure above shows the percentage of suicide decedents with blood alcohol concentrations (BAC) >0.08 g/dL, by race/ethnicity and sex for 17 states during 2005-2006, according to the National Violent Death Reporting System. Among male decedents tested, 25% tested above legal intoxication; among females tested, 18% tested above legal intoxication. Males had a significantly higher percentage with BACs >0.08 g/dL than females (p<0.02, by chi-square test) in all racial/ethic populations except non-Hispanic American Indians/Alaska Natives, for whom the percentages for each sex were equal (37%) (p=0.99, by chi-square test).

Depression

Depression, though not commonly understood, is believed to be the result of interacting genetic, biological, environmental, and psychological factors. Depression, a mood disorder, is a common type of mental health problem in which a variety of symptoms combine to interfere with daily living, causing pain for the person who is depressed and for those who care about or interact with him or her. It takes various forms, including minor depression and major depression. Major depression results in the person being unable to function normally at work, at school, at home. It can even interfere with eating, sleeping and previously pleasurable activities. Some of the forms of depression include psychotic depression, postpartum depression, seasonal affective disorder, and bipolar disorder. Some of the signs and symptoms of depression include:

- Persistent sad, anxious, or "empty" feelings

- Feelings of hopelessness or pessimism

- Feelings of guilt, worthlessness, or helplessness

- Irritability, restlessness

- Loss of interest in activities or hobbies once pleasurable, including sex

- Fatigue and decreased energy

- Difficulty concentrating, remembering details, and making decisions

- Insomnia, early-morning wakefulness, or excessive sleeping

- Overeating, or appetite loss

- Thoughts of suicide, suicide attempts

- Aches or pains, headaches, cramps, or digestive problems that do not ease even with treatment. (NIMH, 2011b)

Illnesses that can accompany depression include anxiety disorders like PTSD, obsessive disorder, panic disorder, social phobia, generalized anxiety disorder, alcohol or other substance abuse or dependence, or other serious medical illnesses such as heart disease, HIV/AIDS, Parkinson's disease. (NIMH, 2011b)

One in five Americans will suffer from a major depression episode at least once in their lifetime, and an equal number will suffer a lesser form of depression. About 19 million, or 10% of US adults suffer from depression each year. (AFSP, 2011c) Risks factors specific to depression include: living with a person who is depressed, a prior history of depression, bereavement, and depressogenic cognitive style. (NIMH, 2011) Other general risks for depression, as well as for other problems, include exposure to trauma, poverty, social isolation, job loss, unemployment, family disruption, dislocation (e.g., immigration), and a history of trauma. (APA, 2011) and (IOM Panel, 2011)

Mental disorders, including depression, can be prevented from developing, as can emotional and behavioral problems. (Beardslee, /2011) In fact, depression often occurs in conjunction with another issue. Addressing that other issue (e.g., stress-management, social skills, or social support) can help prevent, reduce or eliminate the depression. Hence the prevention of depression can be an outcome of an intervention targeting another matter, such as substance abuse prevention or life skills that facilitate employment. (IOM Panel, 2011; Muñoz, Cuijpers, Smit, Barrera, & Leykin, 2010). According to Muñoz, et al, 22% of all major depressive episodes can be prevented. (Muñoz, et al, 2010) Depression is a brain disease and involves neurotransmitters. It is largely preventable and treatable, such that 80 to 90% of persons with depression can be helped by treatment (AFSP, 2011).

In the U.S., 15.6 million children live with an adult who has had a major depression in the last year. (NRC & IOM, 2009b) Prevention approaches can take various forms, including the prevention or reduction of depression in the parent to assist parent and family, targeting the risk and enhancing protective factors of children of depressed parents who are at high risk of depression themselves. Improving parent-child relationship for the benefit of both, and using two-generational approaches that enhance protective factors and address risk factors. (Beardslee, 2010) The main barriers to reducing depression in parents and families are systemic, provider capacity, and financial. In addition to these obstacles, the National Academies Committee (2009b) identified seven critical elements of a successful system of care: multigenerational, comprehensive, available across settings, accessible, integrative, developmentally appropriate, and culturally sensitive.

Anxiety and Stress

Other mental health conditions that can contribute to personal success or to negative health outcomes include anxiety and stress. There is not a firm consensus among psychologists on definitions of stress. The APA Glossary of Terms defines stress as "The pattern of specific and nonspecific responses an organism makes to stimulus events that disturb its equilibrium and tax or exceed its ability to cope." Anxiety like stress is a normal part of life. Anxiety is defined by the same sources as "an intense emotional response caused by the preconscious recognition that a repressed conflict is about to emerge into consciousness." A certain amount of stress and anxiety can actually be healthy.

Stress. There are three ways to view stress: The first focuses on the environment, the stimulus or stressor. The second focuses on a personal reaction of distress. The third focuses on the relationship and interaction between a person and the environment, i.e., coping. When we encounter a potential stressor in our environment, we tend to react with either a fight or flight response, depending in part upon whether we feel we can "cope" with the stressor or not. If not, we react with "distress." The reaction depends furthermore on our past experience, for example, learned helplessness, due to earlier inability to respond (or cope) in a successful manner, resulting in ceasing to try. High demand and low ability to control results in strain. Stress affects our physiology and behavior. Stress can lead to behavioral problems like increased use of alcohol, tobacco or other drugs, caffeine and poor nutrition. It can have physiological impacts on the cardiovascular, immune, digestive, respiratory, and/or endocrine system. Especially when past experiences or other conditions contribute to vulnerability, an exposure to stress will cause physiological and psychological wear and tear and/or coping actions and behavior changes. These can produce precursors or symptoms of illness and ultimately illness or unhealthy behaviors. Coping strategies can focus on controlling the emotional response and/or on the problem to reduce or eliminate it or transform it into a positive opportunity. Coping focused on controlling emotions can take the form of seeking social support, distancing oneself or detach mentally, avoidance or escape, exerting self-control, acting responsibly, and/or finding positive meaning in the initially negative circumstance. Men tend to focus more on the problem, women more on the emotions, but men and women from the same career or occupation tend to respond similarly rather than according to traditional societal gender role. The ability to cope successfully with stress depends upon having social and other kinds of support , such as receiving emotional support, informational support, affirmed feelings of being part of a network, respectful encouragement and validation, and personal assistance from a helpful person. Sometimes the stressor can make it difficult for a person to utilize support system, even becoming so problem-focuses that he/she causes supporters to withdraw. The supporter's reaction sometimes makes a situation worse or the supporter can be negatively impacted by their efforts to help, e.g., caregivers who are overtaxed by the burden of care. Stress management or coping technics can help to reduce stress, Cognitive or relaxation therapy can help people deal with stress. Cognitive therapy analyzes stressors to identify illogical thinking or irrational beliefs that result in exaggeration the problem (catastrophizing), or overgeneralizing, or selective abstraction (focusing on negative details rather than the overall situation which may be much less alarming. Relaxation uses exercises to relax muscles and mental exercises like mental imagery and meditation to control arousal and negative reactions to stressors. (University of Minnesota, n.d.)

Anxiety. In addition to healthy, normal levels of anxiety, Excessive anxiety can become mental health disorders. Anxiety disorders are groups into five major types, including generalized anxiety disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, panic disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and social phobia or social anxiety disorder. Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) is characterized by chronic worry and anxiety, even when there is no cause for concern. Obsessive-compulsive disorder is marked by either repeated undesired thoughts called obsessions or repeated behaviors called compulsions, or both.

A person with panic disorder experiences sudden intense fear along with physiological symptoms like chest pain, shortness of breath or dizziness. Post-traumatic stress disorder can result from witnessing or experiencing a perilous event. In PTSD the normal self-defensive "fight or flight" response is altered to produce stress or fear even when not in any danger. Finally, in social anxiety disorder the person feels overcome with anxiety and extremely self-conscious in all ordinary social settings or in specific settings like public speaking or eating in public. (NIMH 2011c)

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) PTSD is an anxiety disorder that can happen at any age as a result of such traumatic events as assault, domestic abuse, imprisonment, rape, terrorism or warfare. An exact cause is not known, though social, psychological, physical and genetic factors play a role. PTSD alters the body's natural stress responses, including the hormones and neurotransmitters that pass information between nerves. Symptoms include "reliving" disturbing events, avoidance and arousal. A person may detach, feel numb, forget what happened, seem flat in mood, avoid reminders of the traumatic event, and feel hopeless. Arousal problems may include problems concentrating, easily startling, exaggerated responses, hypervigilance, irritability and angry outbursts, and sleep problems. Treatment and a strong social support system can help prevent the development of PTSD after a trauma. In the even of PTSD, treatment called "desensitization" helps many people over time. PTSD is often associated with alcohol and other drug abuse, depression, panic attacks and suicide attempts. Desensitization treatment should follow, not precede, treatment for these aforementioned associated problems.

Many veterans of combat in recent wars are returning home with anxiety disorders, particularly PTSD. About 30 percent of those who spend time in a war zone suffer from PTSD at time of discharge and another 20 to 25 percent will experience partial symptoms. (Nebraska Department of Veterans Affairs, 2007) Estimates of returning veterans from Afghanistan and Iraq with PTSD range from a RAND 2008 study result of 13.8% (Gradus, 2011) to 20 percent (Johnson, 2011). Rates of PTSD and depression have been found to increase markedly among National Guard twelve months post-deployment, while rates remained unchanged among active military. (Carollo, 2010)

Suicide

Over 36,000 persons (a rate of one every 15 minutes) die annually in the U.S. by suicide. (AFSP, 2011) As emphasized by SAMHSA, "the importance of suicide prevention measures during this difficult economic time cannot be overstated." (2011, p. 41)

Mental disorders, especially depression, or an addiction disorder are risk factors in over 90% of suicide deaths. (NIMH, 2011; Moscicki, 2005) There are multiple contributing factors that influence suicide. Across all age groups, mental and addictive disorders are significant risk factors. (Moscicki, 2005) They can be reduced to four categories: biological factors, predisposing factors, proximal factors and immediate triggers. Examples of predisposing factors include mental disorders, substance abuse, personality (depressogenic), and severe chronic pain. Proximal factors include hopelessness, intoxication (e.g., binge drinking), impulsiveness, negative expectancy, and severe pain. Immediate triggers include public humiliation, access to guns, a severe defeat, major loss, and a worsened prognosis. (McKeon, 2011; NIDH, 2011)

Another view, the social ecological model, organizes risk factors into five levels, any number of which may be operating coincidentally. These include individual factors like beliefs and genetics; group or family factors; institutional factors, which can include policies and programs; community factors like resources and services; and public policy and societal factors, including local and national policies and cultural forces. (Saunders, 2008)

Individual risk factors include age and sex (male), mental illness, substance abuse, loss, having previously attempted suicide, personality traits (e.g., impulsiveness and depressogenic cognitive style), poverty, unemployment, incarceration, access to lethal means, failure or academic problems, a history of bullying or violence, exposure to suicide, no longer being married, barriers to health care/mental health care, and feeling like you are a burden to others. Other risk facts include living in a rural or remote area, isolation or social withdrawal and stigma. (McKeon, 2011 )

Protective factors include cultural or religious beliefs that discourage or disapprove of suicide and encourage self-preservation; coping, conflict resolution and problem solving skills; having a family and community support system; having access to effective clinical care for mind, body and substance abuse disorders; support for seeking help; and supportive relationships with medical and mental health care providers. (CDC, 2010) Other protective factors include having clear reasons to live; family cohesion (especially for youth); a sense of social support, interconnectedness, being married and/or a parent, , having people who recognize and respond to warning signs for suicide. Gate keeper training that teaches people what to do next when they see warning signs for suicide is an important prevention approach. (McKeon, 2011)

Death from Suicide.

According to Dr. Richard McKeon of the IOM, risk factors for suicide death include age and sex. The group at very highest risk of death from suicide are elderly white men ages 85+. (NIMH, 2011) More males commit suicide than females by a rate of 4:1. For males, risk increases with age, especially from age 65, when rates become seven time higher than for women ages 65 and older. For women risk is highest from age 45 to 54 and later from age 75. (AFSP, 2011) The rate among the elderly has dropped over the past decades, though there was a spike in 2008 that was the largest increase in forty years.

There is a strong relationship between substance abuse and suicide with 30% of deaths involving BAC over the legal limit and 40% involving alcohol at some level. It is also important to note that the rate of suicides among persons with major depression is eight times higher than the suicide rate for the general population. About 50% of those dying from suicide had suffered major depression. Suicides among military veterans account for as many as 1 in 5 suicides in the U.S. Between 2005 and 2009, over 1100 members of the Armed Services took their own lives. (McKeon, 2011) Firearms are more often used to commit suicide than they are in homicides, and about half of suicides involved firearms. (AFSP, 2011)

Individuals released from in-patient suicide watch hospital units remain at high risk. About 10% of those who die from suicide were discharged from an Emergency Department visit within the past 2 months. About 86% of those hospitalized due to suicidality are predicted to eventually die by suicide. The greatest risk is during the first month after release from inpatient care. More veterans have been found to commit suicide in the first week after release. Very quick follow-up is needed. (McKeon, 2011)

Military and veterans are at higher risk of suicide. As of September, 2011, over the past decade 2,293 active duty military had committed suicide. In comparison, 6,139 had died during that same period in Iraq and Afghanistan. The most common stressors include relationship problems, work-related and financial problems. (Wong, 2011) The rate of suicide deaths among military reached 22 per 100,000 in 2010, much higher than the rate among a similar aged civilian population. (Zoraya, 2011) Though about 1% of Americans have given military service, 20% of all suicides, a rate of 18 per day, are by former members, veterans, of the military service. (Harrell & Berglass, 2011)

One difficulty faced by the military in suicide prevention and treatment efforts is a strong stigma associated with mental health and therapy, which can influence individuals to not seek help. President Obama's recent decision to send letters of condolence to families of servicemen and women who die by suicide has been hailed as a step towards addressing this stigma. (Zoroya, 2011). Two thirds of military suicides occur outside the war zone. At the same time, more than half had served in Iraq or Afghanistan, and for every death by suicide, there were five others who attempted suicide. (Wong, 2011) Many psychiatrists point to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) as a cause of suicide among active military and veterans. (Johnson, 2011) The VA has many current initiatives underway to address this problem, including a 42/7 hotline, 1-800-273-TALK, where a VA specialists responds to vets in crisis. (Harrell & Berglass, 2011)

Suicide Attempts

More adolescents than other age groups attempt suicide. Whereas males die at a higher rate, females attempt suicide three times more often than males. (NFSP, 2011a) Rates peak in adolescence and decline with age. Young LGBT youth and young Latina girls are at higher risk. (McKeon, 2011)

For youth, risk factors for attempts at suicide include depression of another mental disorder, substance abuse or addition, physical or sexual abuse, and disruptive behavior. Adult risk factors include depression, addiction or separation or divorce. (NIMH, 2011)

Cost

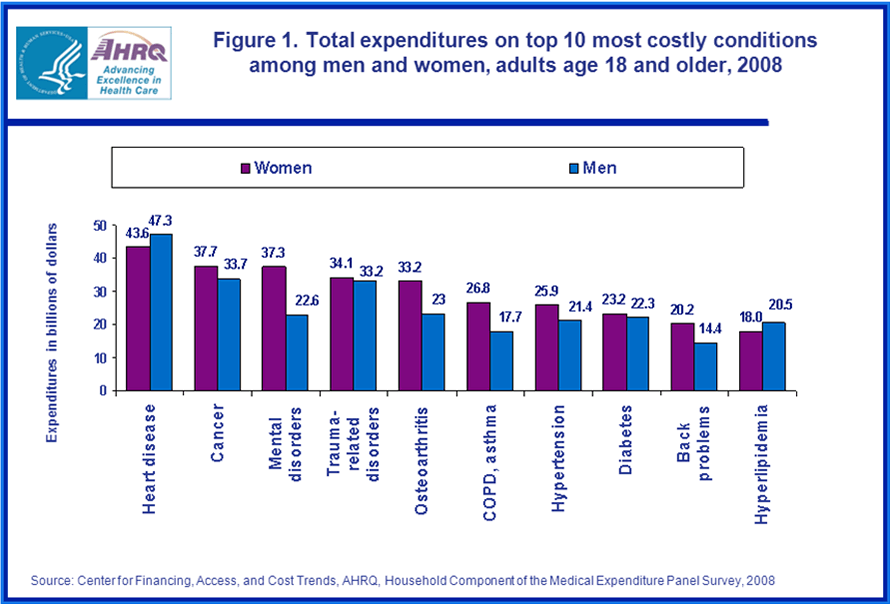

While it cannot compare to the significance of morbidity, mortality and loss of quality of life by those who suffer mental disorders and those who love them and those who live and interact with them, another form of measurement is cost in dollars. The cost in dollars of mental health conditions within the spectrum of all health conditions is revealing. The Medical Expenditures Panel Survey found that mental health disorders are the third most costly health condition for women in the U.S., amounting to $37.3 billion, less only than spending on cancer ($37.7 billion) and heart disease ($43.6 billion). For men, mental disorders ranked fifth and the cost was markedly less (only 60.6% as much at $22.6 million). In terms of numbers there were roughly twice as many women reporting mental disorders as men (21.4 million: 11.4 million). The following table shows total expenditures by gender on top 10 most costly conditions among men and women ages 18 and older in 2008. (Soni, 2011)

The trend in both prevalence and cost has been upward. A larger percentage of adults aged 18-64 incurred expenses, more of their spending went towards prescription medications, and the cost (inflation-adjusted) per ambulatory visit increased from 1997 to 2007. (Brown, 2010)

Prevention -- Mental Health Prevention Programs from SAMHSA

Below is a listing of many prevention programs and initiatives of the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration aimed to improve mental health and prevent mental health problems. Links are provided to give access to additional information. In general, the steps taken to address mental health risks factors and to fortify mental health protective factors are similar to those employed for substance abuse prevention. Just reading through the following list of programs and initiatives from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (2011) underscores the major risk factors and service needs of our populations. It also suggests action steps and resources that can be learned from, engaged in, and/or put to good use.

Suicide Prevention (Garrett Lee Smith Memorial Act Suicide Prevention Program) http://www.spanusa.org/index.cfm?fuseaction=home.viewPage&page_ID=7EBCCC66-B810-BC82-90BD97219C9B7876 and www.sprc.org

This program funds two significant youth suicide prevention programs and a resource center. These programs encourage suicide prevention and early intervention, with private-public collaboration among youth serving agencies. It also extends to higher education. Trains teachers, mental health providers, social service providers, police officers, coaches, and others who interact with youth frequently.

Safe Schools/Healthy Students Program for Youth Violence Prevention (http://www.sshs.samhsa.gov/)

This grant program promotes healthy childhood development and prevention of violence and alcohol and other drug abuse.

National Child Traumatic Stress Network (NCTSI) (http://www.nctsn.org/)

The mission of the NCTSI is to raise the standard of care and improve access to services for traumatized children, their families and communities throughout the United States.

Homelessness Prevention Program (http://homeless.samhsa.gov/)

About 700,000 persons are h homeless each night in the U.S. A quarter of them have serious mental illness (SMI). Over half have alcohol and/or other drug problems. See Homelessness Resource Center,

Project LAUNCH Wellness Initiative (http://projectlaunch.promoteprevent.org/)

Linking Actions for Unmet Needs in Children’s Health aims for optimal functioning across all developmental domains, including physical, social, emotional, cognitive, and behavioral.

Criminal and Juvenile Justice Program (http://aspe.hhs.gov/hsp/11/Incarceration&Reentry/Inventory/SubstanceAbuseandMentalHealthServicesAdministration.shtml)

Jail Diversion Program for Adults moves people with mental illness to more appropriate community-based treatment and recovery support related services.

Community Mental Health Services Block Grant (CMHSBG) (http://dmh.dc.gov/dmh/cwp/view,a,3,q,642799.asp)

Funds 59 states and Territories and provides a “safety net” source of funding for mental health services for the most vulnerable.

Project for Assistance in Transition from Homelessness (PATH) (http://pathprogram.samhsa.gov/)

A unique program to address the needs of persons with serious mental illness (SMI) or SMI with co-occurring substance abuse disorders who are homeless or at risk of homelessness. It aims to connect persons with critical services to assist on the road to recovery, to “escape the revolving door to nowhere.”

Protection and Advocacy for Individuals with Mental Illness (PAIMI) (http://cqc.ny.gov/advocacy/protection-advocacy-programs/paimi)

This program provides casework to children, adolescents, adults and the elderly.

Children in Mental Health Services Program (CMHSP) http://www.samhsa.gov/children/

See also this newsletter: Coordinating Care for Children with Serious Mental Health Challenges http://www.samhsa.gov/samhsanewsletter/Volume_17_Number_4/CoordinatingCare.aspx

The National Mental Health Information Center (NMHIC) http://www.healthfinder.gov/orgs/HR2480.htm

Serves to connect the mental health workforce and the general public to the latest information on prevention and treatment of mental health and substance abuse disorders. It features information on suicide prevention, stigma reduction, women’s mental health, and multiple languages.

SAMHSA’s Health Information Network (SHIN) http://www.cuidadodesalud.gov/enes/dhealthfinder/orgs/HR0027.htm

This resource aims to advance health information technology, to integrate mental health and substance abuse prevention and treatment, to promote anti-stigma campaigns and use of evidence-based programs and practices, and to eliminate mental health disparities.

Conclusion

In summary, mental health is critical to overall health. Wellness -- how a person feels about the quality of his or her life -- matters to health outcomes. Many surveys collect data to measure people's feelings about their quality of life. Mental health problems take many forms and can lead to depression and/or suicide. Poverty is recognized as an important risk factor, especially for children's mental health. Substance abuse and addiction are often co-occurring with mental illness. Depression is a common form of mental illness, sometimes leading to suicide attempts and deaths by suicide. Suicide affects every spectrum of the population and results in devastating loss. The cost to society in human terms is immeasurable and in economic terms is huge. Yet, given that mental illness is usually highly treatable, there is much room for optimism that, if we take appropriate action to prevent, intervene, treat, and give on-going support for recovery, many lives will be saved and quality of life can be significantly enhanced for millions of persons , families, and communities.

This section of the County Profiles will present data relevant to assessing a county's mental health status for specific risk and protective factors and for prevention planning. This section of the County Profiles presents the following data tables related to mental health:

- Mentally Unhealthy Days (Number per month) (CHR, 2011)

- Mental Health Disorder Deaths (Total and by Race-Ethnicity) (Number) (QHDO, 2010)

- Suicide Deaths (Total and by Race) (Number) (QHDO, 2010)

- Suicide Deaths Rates (by Race) (QHDO, 2010)

- Suicide Deaths (Total and by Ethnicity) (Number) (QHDO, 2010)

- Suicide Deaths Rates (Total and by Ethnicity) (QHDO, 2010)

- Suicide Deaths (Total and by Sex) (Number) (QHDO, 2010)

- Suicide Deaths Rates (Total and by Sex) (QHDO, 2010)

- Suicide Deaths (by Race and Sex) (Number) (QHDO, 2010)

- Suicide Deaths Rates (by Race and Sex) (QHDO, 2010)

- Suicide Deaths (by Ethnicity and Sex) (Number) (QHDO, 2010)

- Suicide Deaths Rates (by Ethnicity and Sex) (QHDO, 2010).

- Access to Health Care (Ranking) (CHR, 2011)

- Uninsured Adults (%) (CHR, 2011)

- Mental Health Providers (Number, Rate and Ratio) (CHR, 2011)

- Family and Social Support (Ranking) (CHR, 2011)

- No Social/Emotional Support (%) (CHR, 2011)

Appendix of Additional Information

For additional mental health information at the state level for Indiana, see the following resources:

1. Links to state-level data related to mental health through StateMaster.com (http://statehealthfacts.org)

Variable |

Definition |

Geographic Specificity |

States Expenditure on MH |

State Mental Health Agency, MH per capita expenditure , 2001 |

State (rank 29th) $65 in range of $398 - $26. Weighted ave. $84.78 |

Suicides |

Total number of suicides |

State (rank 15th of 51) 736 in range of 3397 to 36. Weighted ave. 617.3 |

Suicides per capita |

Total number of suicides per capita |

State (rank 26th of 51) 0.117 per 1,000 people |

Resident population with serious mental illness |

Number of people diagnosed with serious mental illness, 2002 |

State (rank 14th of 52) 246,467 |

Resident population with serious mental illness (per capita) |

Number of people diagnosed with serious mental illness (rate per capita), 2003 |

State (37th of 52) 0.393 per 10 |

Serious Psychological Distress |

Percent of residents who have suffered from serious psychological distress or serious mental illness in the past year, 2003-2004. |

State (14th of 51) 10.31% |

Total State Expenditure on MH |

State MH Agency, MH Actual dollar expenditure, 2001 |

State (rank 19th of 51) $394,000,682 |

Total State Expenditure on MH (per $ GDP) |

State MH Agency, MH Actual dollar expenditure as amt per $ GDP, 2001 |

State (rank 28th of 51) $0.17 per $100 of GDP |

Total State Expenditure on MH (per capita) |

State MH Agency, MH Actual dollar expenditure per capita, 2001 |

State (rank 29th of 51) $62.82 |

2. The State Health Access Data Assistance Center (http://www.shadac.org) posts American Community Health Survey data from the U.S. Census Bureau about trends in the public's rates of health insurance coverage and access to care. The American Community Survey ranks the states for the following variables:

- % of population w/ health insurance, 2009

- % of employers offering insurance, 2009

- % of employees in establishments that offer health insurance, 2009

- at firms offering coverage, % of employees eligible, 2009

- % of eligible employees enrolling in health insurance offered by employers, 2009

- % of premiums contributed by employees enrolled in employer-sponsored single coverage, 2009

- % of premiums contributed by employees enrolled in employer-sponsored family coverage, 2009

- Medicaid enrollment as a % of population under 200% FPL, 2009

- % of population at or above 200% FPL, 2009

- Active patient care physicians per 100,000 population, 2008

- Hospital beds per 100,000 population, 2008

- % of population w/ a personal doctor or health care provider, 2009

- % of population that could get medical care when needed, 2009

- FQHC clinic sites per 100,000 population under 200% FPL, 2009

-

% of hospitals publicly owned by state or local governments, 2008

Patients served by FQHCs as a % of population under 200% FPL, 2009

The web site reports the following statistics for Indiana with comparison to the US:

Health Insurance Coverage & Income [*]

IN

US

% of population w/ health insurance, 2009

85.80%

84.60%

% of employers offering insurance, 2009

49.10%

55.00%

% of employees in establishments that offer health insurance, 2009

84.80%

87.60%

at firms offering coverage, % of employees eligible, 2009

82.50%

79.50%

% of eligible employees enrolling in health insurance offered by employers, 2009

73.10%

76.90%

% of premiums contributed by employees enrolled in employer-sponsored single coverage, 2009

22.10%

20.50%

% of premiums contributed by employees enrolled in employer-sponsored family coverage, 2009

25.30%

26.70%

Medicaid enrollment as a % of population under 200% FPL, 2009

41.10%

45.60%

% of population at or above 200% FPL, 2009

64.30%

65.30%

System-Wide Health Care Resources [**]

IN

US

Active patient care physicians per 100,000 population, 2008

193

220

Hospital beds per 100,000 population, 2008

276

270

% of population w/ a personal doctor or health care provider, 2009

83.50%

72.60%

% of population that could get medical care when needed, 2009

83.40%

81.50%

Safety-Net Resources [***]

IN

US

FQHC clinic sites per 100,000 population under 200% FPL, 2009

3.2

6.8

% of hospitals publicly owned by state or local governments, 2008

31.70%

22.10%

Patients served by FQHCs as a % of population under 200% FPL, 2009

11.20%

17.30%

3. The U.S. Health and Human Resources, Office of Women's Affairs web site titled Quick Health Data Online (QHDO) at http://www.healthstatus2020.com includes extensive data by state and county.

- Adult Mental Health Statistics - State

- Adult Mental Health Statistics, Age Adj - State

- Adult Mental Health Statistics, Age Adj 3 Yr Avg - State

- Mental Disorder Death Rates - State

- Mental Disorder Deaths, by Sex and Race

- Suicide Deaths, by Sex and Race

- Suicide Death Rates, by Sex and Race

- Suicide Death Rates, by Sex and Race, Age Adj

- Suicide-Related Behaviors in Youth - State

Additional Resources:

Statistics on medical expenditures. US Department of Health and Human Services. Medical Expenditures Panel Survey. Retrieved 10-31-2011. http://www.meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/. For Statistics on expenditures for mental health services, including mental health, access to care, coverage, the uninsured, and children, men, women, and the elderly’s health.

Stress. Stanford University School of Medicine. Center on Stress and Health. 2011. Retrieved 10-31-2011. http://stresshealthcenter.stanford.edu/

Men’s mental health. Mind for Better Health. Men’s Mental Health. 2011. Retrieved 10-31-2011. http://www.mind.org.uk/help/people_groups_and_communities/mens_mental_health

Gender and Mental Health. World Health Organization, Gender and Mental Health, 2002. . Retrieved 10-31-2011. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/gender/2002/a85573.pdf

Mental Health. Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Retrieved 10-31-2011. http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/mentalhealth/home.html

VA Suicide Prevention 24/7 Crisis hotline All 1-800-273-TALK and then “push 1” to reach a trained VA professional who can deal with an immediate crisis.

Selected Bibliography

A.D.A.M ., Inc. (2011) Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder PTSD. A.D.A.M. Medical Encyclopedia. (Reviewed

March 5). Retrieved 10-31-2011 from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmedhealth/PMH0001923/

American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (AFSP) (2011a) Facts and figures. Retrieved 10-25-2011 from http://www.afsp.org/index.cfm?fuseaction=home.viewpage&page_id=050fea9f-b064- 4092-b1135c3a70de1fda.

American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (AFSP) (2011b) Risk factors for suicide. Retrieved 10-25-

2011 from http://www.afsp.org/index.cfm?fuseaction=home.viewPage&page_id=05147440-

E24E-E376-BDF4BF8BA6444E76

American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (AFSP) (2011c) Risk factors for depression. Retrieved 10-

23-2011 from http://www.afsp.org/files/College_Film/factsheets.pdf.

American Psychological Association (APA) (2011) “Statistical risk factors for suicide,” Monitor on

Psychology 32/10. Retrieved 10-25-2011 from http://www.apa.org/monitor/nov01/suiciderisk.aspx

Annie E. Casey Foundation (2011) Kids Count Data Center. Retrieved 10-21-2011 from http://datacenter.kidscount.org/

Beardslee, WR. (2010) “Recent advances in the prevention of depression.” 6th World Mental Health Conference. Washington, DC. Nov. 17. The National Academies. Retrieved 10-25-2011 from http://wmhconf2010.hhd.org/sites/wmhconf2010.hhd.org/files/recent%20advances%20in%20t he%20prevention%20of%20depression.pdf

Beardslee, WR, Chien PL, Bell CC. (2011) “Prevention of mental disorders, substance abuse, and problem behaviors: a developmental perspective,” Psychiatric Services 62/3:247-254.

Bisggaier J, Rhodes KV. (2011) Cumulative adverse financial circumstances: associations with patient health status and behaviors. Health Social Work 36/2:129-137.

Bloch G, Rozmovits L, Giambrone B. (2011) Barriers to primary care responsiveness to poverty as a risk factor for health. BMC Family Practice 29/12:62

Boden JM, Fergusson DM. (2011) “Alcohol and depression,” Addiction 106/5:906-14. Epub, Mar 7.

Brown, Erwin, Jr. (2010) STATISTICAL BRIEF #319: Health Care Expenditures for Adults Ages 18-64 with a Mental Health or Substance Abuse Related Expense: 2007 versus 1997. Retrieved 10-31-2011 from http://www.meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/data_files/publications/st319/stat319.pdf

Carollo, Kim. (2010) Combat’s Hidden Toll: 1 in 10 Soldiers Report Mental Health Problems,” ABC News.

Retrieved 10-31-2011 from http://abcnews.go.com/Health/MindMoodNews/10-soldiers-fought-

iraq-mentally-ill/story?id=10850315

Center for Mental Health Services (CMHS) (2011) Transformation Accountability (TRAC), NOMS client- Level Measures for Discretionary Programs Providing Direct Services, Services Tool, Child or Adolescent Respondent Version, Version 7, Expiration Date 5/21/2013. SAMHSA.

Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. (CSAT) (2008) Substance Abuse and Suicide Prevention: Evidence and Implications - A White Paper. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration (SAMHSA). Retrieved 10/23/2011 from

http://www.samhsa.gov/matrix2/508SuicidePreventionPaperFinal.pdf

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2011a) Mental Health: Well-Being. Retrieved 10-24-

2011 from www.cdc.gov/mentalhealth/data_stats/well-being.htm, July 1, 2011

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2011b) Health Related Quality of Life: Well-Being

Concepts. Retrieved 10-24-2011 from http://www.cdc.gov/hrqol/wellbeing.htm, March 17,

2011

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2011c) Mental Health: Health Related Quality of Life.

Retrieved 10-24-2011 from www.cdc.gov/mentalhealth/about_us/hrql.htm, July 1, 2011

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2010) Injury: Violence Prevention. Suicide: Risk and

Protective Factors. Retrieved 10-25-2011 from http://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/suicide/riskprotectivefactors.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2009) “Alcohol and Suicide Among Racial/Ethnic

Populations --- 17 States, 2005-2006,” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly (MMWR) 58/23: 637-

641.

Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) (2011) The World Fact Book. Country Comparison-Life Expectancy at Birth. Retrieved 10-24-2011 from https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world- factbook/rankorder/2102rank.html

Child Stats.gov (2011) America’s Children: Key National Indicators of Well-Being. ECON1.A Child poverty: Percentage of all children and related children ages 0-17 living below selected poverty levels by selected characteristics, 1980-2009. Retrieved 10-24-2011 from

http://www.childstats.gov/americaschildren/tables/econ1a.asp?popup=true

Department of Veterans Affairs. (2011) Fact Sheet: VA Suicide Prevention Program, Facts about Veteran Suicide. Retrieved 11-2-2011 from www.erie.va.gov/pressreleases/assets/SuicidePreventionFactSheet.doc

Duncan G, Ziol Guest K, Kalil A. (2010) “Early-childhood poverty and adult attainment, behavior, and health,” Child Development 81/1:306-325.

Gradus, Jaimie L.. (2011) Epidemiology of PTSD. Department of Veterans Affairs. National Center for

PTSD. Retrieved 10-31-2011 from http://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/pages/epidemiological-facts-ptsd.asp

IndexMundi (2011) County comparison - Population below poverty line. Retrieved 10-24-2011 from

http://www.indexmundi.com/g/r.aspx?v=69, January 1, 2011 adu

Harrell, Margaret C. & Berglass, Nancy. (2011) Losing the Battle: The Challenge of Military Suicides.

Center for a New American Society. Retrieved 11-2-2011 from http://www.cnas.org/files/documents/publications/CNAS_LosingTheBattle_HarrellBerglass.pdf

Institute of Medicine (IOM) (2011) Institute of Medicine (IOM) Panel (Tony Biglan, Irwin Sandler and William Beardslee). National Prevention Network Prevention Research Conference, Atlanta, GA, Sept.22.

Johnson, Lorie. (2011) PTSD: Conquering Military Suicides with Hope (Jan 9). CBN News. Retrieved 10-

31-2011 from http://www.cbn.com/cbnnews/healthscience/2010/October/Ministry-Arms-US-

Military-to-Conquer-PTSD-/

Krohn MD, Lizotte AJ, Perez CM (1997)The interrelationship between substance use and precocious transitions to adult statuses. J Health Soc Behav 38(1):87-103, 1997.

Lançon C. (2010) [Depression and health state] Encephale 36/Suppl 5:S112-6.

Leve LD, Fisher PA, Chamberlain P. (2009) “Multidimensional treatment foster care as a preventive intervention to promote resiliency among youth in the child welfare system,” Journal of Personality 77/6:1869-902. E-publication Oct 6.

McKeon, R. (2011) “Preventing suicide and substance abuse: why collaboration is important.” National

Prevention Network Prevention Research Conference, Atlanta, GA, Sept.23.

Mental Health America. Building social support: It’s Good for your Health. Retrieved 11-1-2011 from http://www.nmha.org/go/mental-health-month/building-social-support

Moscicki, E. (2005) Epidemiology of Suicide. International Psychogeriatrics 7/2 (1995):137-148.

Published online Jan. 7, 2005.

Muñoz RF, Cuijpers P, Smit F, Barrera A, and Leykin Y. (2010) “Prevention of Major Depression,” Annual

Review of Clinical Psychology 6:181-212.

The National Academies. (2009) Mary Jane England and Leslie J. Sim, Editors. Committee on Depression, Parenting Practices, and the Healthy Development of Children; National Research Council; Institute of Medicine “Depression in Parents, Parenting and Children: Opportunities to Improve Identification, Treatment and Prevention,” Brief Report. (June). Retrieved 10-25-2011

from http://www.bocyf.org/parental_depression_brief.pdf

National Center for Children in Poverty.(NCCP) (2011) Child Poverty. Retrieved 10-24-2011 from

http://www.nccp.org/topics/childpoverty.html 2011

National Institute for Drug Abuse (NIDA) (2011) Preventing Drug Abuse: The Best Strategy. Retrieved

11-1-2011 from http://drugabuse.gov/scienceofaddiction/strategy.html

National Institutes of Health (2011) Depression. Retrieved 10-26-2011 from

http://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/depression/depression-booklet.pdf

National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) (2011a) Suicide in the U.S.: Statistics and Prevention.

Retrieved 10-23-2011 from http://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/suicide-in-the-us-

statistics-and-prevention/index.shtml

National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) (2011b) Depression. Retrieved 10-26-2011 from

http://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/depression/complete-index.shtml

National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) (2011c) Anxiety Disorders. Retrieved 10-30-2011 from

http://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/anxiety-disorders/index.shtml

National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) (2011d) National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH)

homepage. Retrieved 10-31-2011 from http://www.nimh.nih.gov/index.shtml

National Research Council (NRC) and Institute of Medicine (IOM) (2009a) Preventing Mental, Emotional, and Behavioral Disorders Among Young People: Progress and Possibilities. Committee on the Prevention of Mental Disorders and Substance Abuse Among children, Youth, and young Adults: Research Advances and Promising Interventions. Mary Ellen O’Connell, Thomas Boat, and Kenneth E. Warner, Editors. Board on Children, Youth, and Families, Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

National Research Council (NRC) and Institute of Medicine (IOM) (2009b) Depression in Parents, Parenting and Children: Opportunities to Improve Identification, Treatment and Prevention. Mary Jane England and Leslie J. Sim, editors. Committee on Depression, Parenting Practices, and the Healthy Development of Children. The National Academies.

Nebraska Department of Veterans Affairs. (2007) Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. Retrieved 10-31-2011 from http://www.ptsd.ne.gov/what-is-ptsd.html

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (2011) Income Distribution - Poverty.

Retrieved 10-24-2011 from

http://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=poverty, October

2011

Pridemore WA, Snowden, A. (2009) “Reduction in suicide mortality following a new national alcohol policy in Slovenia: An interrupted time-series analysis,” American Journal of Public Health

99/5:915-920. Retrieved 10-22-2011 from

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2667837/

Santen, David. (2010) OHSU-PSU Research Identifies Hidden Epidemic: Suicide Rate Among Young

Women Veterans More Than Twice That of Civilians. Portland State University. Retrieved 10-26-

2011 from

http://www.pdx.edu/news/ohsu-psu-research-identifies-hidden-epidemic-suicide-

rate-among-young-women-veterans-more-twice

Saunders Goldstein I., compiler. (2008) “It takes a community:” Report on the summit on opportunities for mental health promotion and suicide prevention in senior living communities. Gaithersburg, MD: SAMHSA. Retrieved 10-25-2011 from http://www.sprc.org/library/It_Takes_A_Community.pdf

Soni, A. (2011) Top 10 Most Costly Conditions among Men and Women, 2008: Estimates for the U.S.

Civilian Noninstitutionalized Adult Population, Age 18 and Older. Statistical Brief #331. July 2011. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. Retrieved 10-31-2011 from

http://www.meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/data_files/publications/st331/stat331.shtml

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration (SAMHSA) (2011) Department of Health and

Human Resources Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration: Fiscal Year

2011. Justification of Estimates for Appropriations Committees. Retrieved 10-27-2011 from http://www.samhsa.gov/Budget/FY2011/SAMHSA_FY11CJ.pdf

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (1999) Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General-Executive Summary. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Mental Health Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Mental Health. Retrieved 10-31-2011 from

http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/mentalhealth/summary.html

University of Minnesota, Department of Psychology (n.d.) Introduction to Health Psychology. Retrieved

10-30-2011 from http://www.psych.umn.edu/courses/spring07/kramerm/psy3617/lectures/lecture_23_health_psychology.pdf

World Health Organization. Depression. Retrieved 11-1-2011 from http://www.who.int/mental_health/management/depression/definition/en/

Wong, Kristin. (2011) “Rising Suicides Stump Military Leaders,” ABC News (September 27). Retrieved 10-

31-2011 from http://abcnews.go.com/US/rising-suicides-stump-military-

leaders/story?id=14578134

Zoraya, Gregg. (2011) Obama Approves Condolence Letters in Military Suicides,” USA Today (July 7).

Retrieved 10-31-2011 from http://www.usatoday.com/news/washington/2011-07-06-Obama-

military-suicides-Army-Chiarelli_n.htm

A total of 8,059 students 18-25 years

of age from 23 Indiana colleges participated in the Indiana College Substance Use Survey conducted in Spring 2021.

A total of 8,059 students 18-25 years

of age from 23 Indiana colleges participated in the Indiana College Substance Use Survey conducted in Spring 2021.